New Atrial Fibrillation Guide

New atrial fibrillation treatment guidelines from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology clarify the role of novel oral anticoagulants and rate/rhythm control medications. Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) may ask about the new guidelines issued by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC). These new guidelines, copublished online on March 28, 2014, in the and, discuss the role of evolving treatment strategies and new drugs in patients with AF, based on the most up-to-date scientific evidence.

The new guidelines replace the previous recommendations—the and 2 incremental to that guideline, the last of which was published in 2011. Key Points:. Risk scoring using the CHA 2DS 2-VASc score and patient preference based on the risks and benefits of therapy should help decide whether or not to initiate anticoagulation. Warfarin is still the only recommended therapy in patients with mechanical heart valves, and use of dabigatran is specifically not recommended in patients with mechanical heart valves.

New Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines 2018

Patients with nonvalvular AF have a choice among warfarin and the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs). The level of evidence supporting use of NOACs is lower (level B) than warfarin (level A), but use of warfarin requires more monitoring. Monitoring in patients taking warfarin should include an international normalized ratio (INR) level measured at least every week when starting therapy and at least every month after achieving a therapeutic INR (usually 2.0 to 3.0).

When patients taking an anticoagulant (either warfarin or a NOAC) are preparing for surgery, some patients (eg, those with mechanical heart values or those with high cardiovascular risk) may require temporary replacement of antithrombotic therapy with unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin. Patients who fail to maintain a therapeutic INR with warfarin should receive a NOAC. Because data on NOAC safety and efficacy (even at reduced doses) is lacking in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment, NOACs require, at minimum, yearly monitoring of renal function. Patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease and patients undergoing hemodialysis should receive warfarin instead of a NOAC. Patients with infrequent episodes of AF may continue to use long-term therapy for AF with an antiarrhythmic drug, but patients with permanent AF should not receive long-term therapy with antiarrhythmic drugs for rhythm control. Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and beta blockers are antiarrhythmic drugs, but offer rate control (not rhythm control) so these drugs can still be used long term in patients with permanent AF.

For patients with infrequent, well-tolerated recurrences of AF who are receiving maintenance therapy with antiarrhythmic drugs, amiodarone may be used after failure of other antiarrhythmic medications (eg, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers or beta-blockers) due to the potential that may arise with amiodarone use. History of visual arts. Patients with permanent AF using dronedarone are at increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular death.

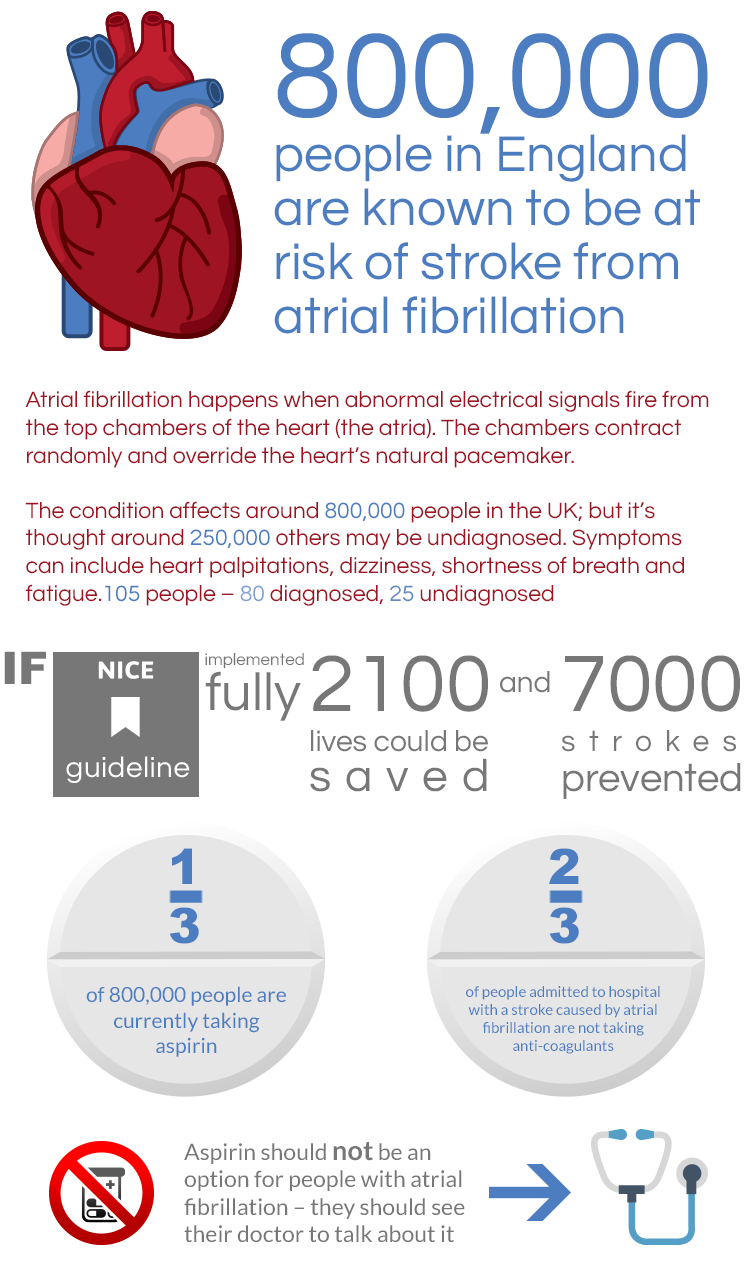

As a result, use of dronedarone in patients with permanent AF is not recommended. In addition, dronedarone should not be used in patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure, or in patients who have had an episode of decompensated heart failure within the past 4 weeks. For patients undergoing electrical shock (electrical cardioversion) to break the pattern of the abnormal AF rhythm and restart the heart’s normal sinus rhythm, guideline authors recommend attaining a therapeutic INR level for at least 3 weeks before and 4 weeks after the cardioversion procedure to reduce the risk of dislodging a thrombus after cardioversion. In patients with AF or atrial flutter of less than 48 hours' duration who also have a high risk of stroke, immediate cardioversion may be necessary; anticoagulation with heparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin (eg, enoxaparin), or a NOAC may be used immediately before cardioversion and afterwards long-term anticoagulation therapy should be initiated. In some cases, when immediate cardioversion is necessary, a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) may help the physician detect clots in the heart before proceeding with cardioversion. The guidelines mention several exceptions and therapeutic considerations for patients with certain disease states (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, AF complicated by acute coronary syndrome, hyperthyroidism, pulmonary diseases, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, pre-excitation syndromes, heart failure, familial AF, and patients who have undergone cardiac surgery). (AF) is a condition of uncoordinated contractions of the ventricles and atria of the heart that may lead to pooling of blood in the atria and ventricles of the heart, leading to clot formation.

These clots can then travel to the brain and other parts of the body, increasing the risk of stroke. Available treatments include rate and rhythm control, electrical cardioversion, and anticoagulation. With the approval of 3 new oral anticoagulant agents in recent years, the new guidelines clarify the role of these agents and update the role of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with AF. Diagnosis, Risk Factors and the Decision to Initiate Treatment Several risk factors increase the risk of AF, including conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, hyperthyroidism, thickening of the left ventricle, heart failure, having undergone cardiothoracic surgery, and a prior myocardial infarction (MI). In addition to comorbidities that increase the risk of AF, abnormalities in certain biomarkers (eg, B-type natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein), genetic factors (eg, European ancestry, family history), and lifestyle factors (eg, alcohol use, smoking, and exercise) may also increase the risk of developing AF. Risk factors alone and clinical suspicion are not sufficient for diagnosis of AF.

Even in patients with several risk factors who are highly likely to have AF, an electrocardiogram is always necessary to establish the diagnosis. AF may be classified as paroxysmal (abnormal rhythm terminates in 7 days), or permanent (a decision has been made to stop attempting to reestablish normal sinus rhythm).

After diagnosis, physicians may use the CHA 2DS 2-VASc score (see Table 1 and Figure 1) to help select patients who are appropriate candidates for anticoagulation therapy. For instance, in patients with nonvalvular AF with a CHA 2DS 2-VASc score of 0, no treatment is recommended, but with a score of 1, an oral anticoagulant or aspirin may be considered, while a score of 2 or greater may necessitate treatment with warfarin or a NOAC. Table 1: Figure 1: Treatments: Anticoagulants Warfarin is still the only recommended therapy in patients with mechanical heart valves (and dabigatran is specifically not recommended in patients with mechanical heart valves). In patients with nonvalvular AF, however, a variety of therapeutic options now exist in addition to warfarin, including, and.

As a group, these are known as novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs). In the guidelines, the evidence supporting use of NOACs is rated lower (category B) than the evidence supporting warfarin use (category A). Despite the slightly lower level of evidence supporting use of NOACs, the guidelines point out that considerable monitoring requirements must be met for effective use of warfarin. In addition to the need for additional anticoagulation early in treatment for some patients, warfarin therapy requires monitoring of the international normalized ratio (INR) at least once a week until a therapeutic INR is attained. Even after attaining a therapeutic INR, the guidelines recommend INR monitoring at least once monthly during maintenance treatment.

Although some patients may do well on warfarin, many patients fail to achieve and maintain consistent therapeutic INR levels. In these patients, the guidelines now recommend use of NOACs.

The new guidelines also clarify the importance of monitoring in patients taking NOACs—an issue that had been unclear since the introduction of these agents. The new guidelines recommend reevaluation of renal function in patients using NOACs at least once per year. Renal function monitoring is important in patients taking NOACs because, in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease, warfarin may be a safer option than NOACs. Under the new guidelines, warfarin is preferred over NOACs in patients undergoing hemodialysis or in patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease (ie, creatinine clearance CrCl 48 hours’ duration or unknown duration receive a course of anticoagulation before undergoing cardioversion. In patients with atrial flutter or AF that has already lasted more than 48 hours (or when the duration of symptoms is unknown), the guideline authors recommend attaining a therapeutic INR level for at least 3 weeks before and 4 weeks after the cardioversion procedure to reduce the risk of dislodging a thrombus after cardioversion. In patients with atrial flutter or AF with a duration.

Pharmacy Times® is the #1 full-service pharmacy media resource in the industry. Founded in 1897, Pharmacy Times® reaches a network of over 1.3 million retail pharmacists. Through our print, digital and live events channels, Pharmacy Times® provides clinically based, practical and timely information for the practicing pharmacist.

Features and specialized departments cover medication errors, drug interactions, patient education, pharmacy technology, disease state management, patient counseling, product news, pharmacy law and health-system pharmacy. Pharmacy Times Continuing Education™ (PTCE) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) as a provider of continuing pharmacy education.